The Rules of Sentence Construction

Syntax is the set of rules that governs how words are arranged to form meaningful sentences. Think of it as the grammatical blueprint for a language. In English, a common structure is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO), as in “The student reads a book.” This order is critical for clarity. If we rearrange it to “Book a reads student the,” the sentence becomes incomprehensible, even though the words are the same. These rules are processed unconsciously, allowing us to produce and understand complex thoughts almost instantly. This system is not universal; other languages follow different rules, such as Subject-Object-Verb (SOV). The brain’s ability to master a specific syntactic structure during childhood is a fundamental aspect of language acquisition, demonstrating a remarkable capacity for rule-based learning and pattern recognition. This process is highly efficient, enabling fluid communication without conscious thought about grammatical rules.

Order is the shape of reason.

Generative Grammar: Creating Infinite Meaning

A fascinating aspect of syntax is its generative power. This concept, largely developed by linguist Noam Chomsky, posits that a finite set of syntactic rules enables us to generate and comprehend an infinite number of unique sentences. You can understand a sentence you have never heard before because your brain recognizes its underlying grammatical structure. For example, you can endlessly embed clauses within sentences (“She thinks that he knows that they believe…”) and still make sense of it. This creative capacity is a hallmark of human language. It means we are not simply memorizing and repeating sentences; instead, we possess a cognitive algorithm for language. This internal grammar allows for the flexibility, creativity, and complexity that characterizes human communication, distinguishing it from simpler animal communication systems which are often fixed and limited in scope.

Syntax Beyond Spoken Language

Does syntax apply to other systems, like music or code?

Yes, the concept of a rule-based system for combining elements—the core idea of syntax—extends beyond human language. In computer science, programming languages have rigid syntax rules. A single misplaced comma or parenthesis can prevent a program from running, demonstrating a strict adherence to structure. In music, syntax refers to the principles of harmony, rhythm, and melody that govern how notes are combined to create a coherent piece. A melody that violates these rules can sound dissonant or random. This suggests that the human brain may possess a more general ability to detect and process rule-based patterns, whether in language, sound, or logical systems. Some cognitive scientists propose that the neural mechanisms that evolved for language syntax might have been adapted from or share resources with other cognitive domains that also rely on structured, hierarchical processing.

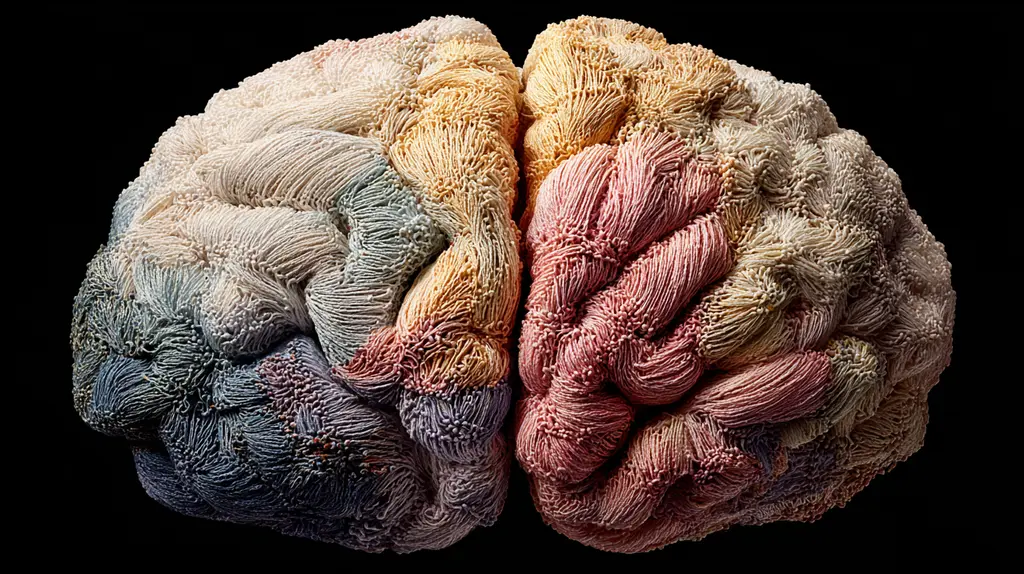

Where is syntax processed in the brain?

Syntactic processing is primarily handled by a specific region in the brain known as Broca’s area, located in the posterior inferior frontal gyrus of the left hemisphere. This area is crucial for both producing grammatically complex sentences and understanding them. When you speak, Broca’s area helps you organize words into the correct grammatical order. When you listen, it helps you parse the structure of someone else’s speech to extract its meaning. Neuroimaging studies, such as fMRI, consistently show activation in Broca’s area when participants engage in tasks that require syntactic analysis, like judging the grammatical correctness of a sentence. This specialization indicates that our brains have dedicated neural hardware for managing the complex rules of grammar, which is essential for our sophisticated language abilities. The precise function and connectivity of this area are still major topics of research in cognitive neuroscience.

What happens when syntax processing fails?

When Broca’s area is damaged, often due to a stroke or brain injury, a person may develop a condition called agrammatic aphasia. This disorder directly impacts the ability to process and produce syntax. Individuals with this condition struggle to form grammatically correct sentences. Their speech is often described as “telegraphic”—it consists of short, simple phrases that omit function words like ‘the,’ ‘is,’ and ‘in.’ For example, instead of saying “I am going to the store,” they might say “I go store.” While they often know the content words (nouns and verbs), they lose the ability to assemble them using the grammatical rules of syntax. This condition starkly illustrates how essential syntax is for fluid communication. The loss of this ability demonstrates that meaning is derived not just from words themselves, but from the structural relationship between them, a relationship managed by specific brain regions.

- LVIS Neuromatch – Explore advanced AI solutions for neuroscience.

- Neuvera – Discover more about cognitive assessment and brain health.